I am reading two books by Ivor Leclerc, The Nature of Physical Existence (1972) and The Philosophy of Nature (1986). This is the second in a series of posts examining his thesis that the philosophy of nature was abandoned with the emergence of modern science and needs to be revisited, particularly the idea of “atoms.”

The Loss of Philosophy of Nature

Let me start with some questions.

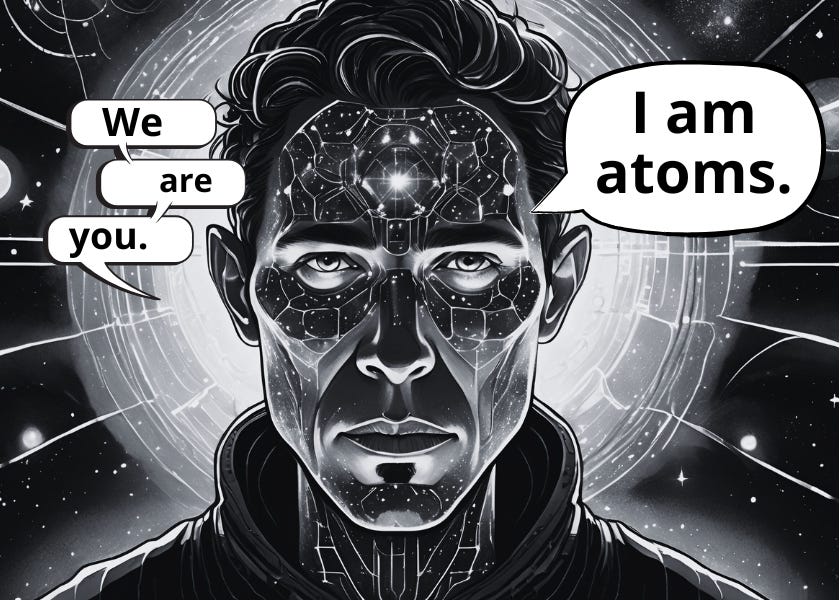

What are you? By that I mean, what is your philosophy of your own existence? Are you the atoms that make up your body? Or are you something beyond particles that whirls your particles, including those that come and go with each meal, into your very self. This is to ask: what is your nature?

“Nature” is one of those words you think you know until you think about it. Nature is the world, right? Science studies nature, i.e., the world around us. Philosophy of nature is the understanding of the way the world is. But does that mean the world is just matter? Or is it matter and something else? How do we answer those questions and, more importantly, how do we know if we are right? Science studies the world, is knowledge of the world, but we need a philosophical framework in which to understand science. Since we are part of the world, this means that we need to understand what we mean by “nature” to understand the universe and our role in it. Despite the significance of a robust philosophy of nature, Ivor Leclerc says that “in the twentieth century this field is receiving singularly little attention from philosophers” (1986, p. 19). The phrase seems obsolete because the word “nature” has ceased to have philosophical meaning.

Leclerc explains that in the seventeenth century with the emergence of modern science, philosophers were aware that Newtonian physics changed the way they thought of nature. It was a departure from the long-held Aristotelian framework. As physicists and philosophers ran into unsolvable contradictions, they set the question aside, and they have remained on the shelf into the twenty-first century. What is needed today is a review of the antecedent theory of nature that was lost, namely the Aristotelian view, and a restoration of it in the context of modern scientific discovery—not just to catch us up but also because the mechanistic and mathematical conceptions of nature with classical and quantum physics have already failed and are being rejected. We are left philosophically bereft.

Aristotle’s Conception of Nature (Yet Again)

I have read many books on philosophy that review Aristotle’s physics and metaphysics. These are fundamental ideas for tackling the problem of restoring the philosophy of nature because it would be unwise to disregard an antecedent theory when seeking to develop a new one. To start this journey, then, we must have a clear understanding of Aristotle’s basic tenets. Leclerc’s summary of Aristotle’s physics is one of the best, most concise I have read (or maybe I am just getting more comfortable with the terms), so I will run through it here but in words that make sense to me. You can find his summary in pp. 20-22 of The Philosophy of Nature (1986) linked above.

The Greek word for “nature” was physis and it meant a being, something existent. A being has in itself a source of change. The process of change is its becoming. A being is something that is becoming what it is according to its nature. Natural being is opposed to artificial things in that the latter do not have this internal source of change, and therefore an artifact’s being is not dependent on nature or itself but on an artificer or artist, who is a natural being, like when a man builds a table or a Tesla. There are questions I have about what is truly artificial versus natural in terms of chemistry, but I will not deal with that for now since the first goal is to understand Aristotle. For him, nature and being are mutual.

If Aristotle asked about the nature of a being, he wanted to know what it is. The standard of being is a living thing, a human, a cow, a rosebush, and the living thing is always, so long as it is living, in the process of becoming. To exist, a being must be becoming what it is. Aristotle did not conceive of living things as stagnate and unchanging, for that would be death. Genesis is the becoming, the inner process of change; corruption is to cease to be becoming.

The idea that natural beings have an inner process of change is, then, the reason for the concepts of actualization and potentiality, which in turn tie in the terms matter and form. (Remember these from Aquinas’s First Way?) Leclerc puts it like this, tying the Greeks words to English:

This process of actualization is ultimately analyzable in terms of eidos, “form,” and hyle, “matter.” Actualization is the energeia, “enacting,” of eidos, “form,” “definiteness.” The concept of hyle is an essentially correlative one; that is, hyle is not understandable on its own, apart from form, but only in reference to form. (1986, p. 21)

This is a most important point! What exists is formed matter, not just matter and not just form, as if the two are independent beings themselves. Something that physically exists is a composite of matter and form (also known as a substance). Aristotle’s view of nature is hylomorphism. Both living (most properly called beings) and non-living (also beings in a lesser sense) things are matter-form composites, i.e., substances.

“Nature” used as a collective noun means the totality of physically existing things, the whole universe constituting a cosmos, an “order.” For Aristotle, to study physically existing things, one must inquire into the four causes. The material cause is the matter out of which a being comes to be. The efficient cause is the source or agent from which a being comes to be. The formal cause is the form or definiteness which determines what a being comes to be. The final cause is that for the sake of which a being comes to be. The final cause is the reason the efficient cause forms the matter into the being.

These basics must be grasped in order to understand how the philosophy of nature changed with the emerging discovery of the elements on the periodic table and atomic theory. Aristotle opposed the teaching of Democritus and his atomos, “atoms” that are indivisible particles in a void, and the objections still apply in many ways to modern atomic theory. I’ll get to that later.

What Was Lost?

In the early seventeenth century, scholars recognized that humans, animals, and plants are unitary wholes, but there was a “growing conviction” (as Leclerc puts it) among the chemists that beings are not unitary wholes but instead made up of smaller unitary wholes (1986, p. 22). In this prelude to atomism, it follows that hylomorphism, along with the four causes, actualization and potentiality, and the nature of a being, were also dismissed. In place of Aristotelian nature, thinkers in the later part of the century began to describe “atoms” at themselves material objects that make up all things—not just material objects but as matter itself. The primary physical existents came to be thought as atoms, and material atomism emerged as a radically new philosophical concept. The idea of matter as something purely potential and non-existent except as formed matter being actualized was completely lost.

The consequence of this view is that people no longer thought of a human, an animal, or a plant as natural beings with an inner source of change but instead as bodies made up of particles. Living things are still seen as growing and changing, but not because of their nature. They are thought to grow and change because of their atoms. The bottom-up view of modern science replaced the top-down view of Aristotelian natural philosophy. I contend that it wrecked humanity.

Leclerc is Right—I Lived It

I mean; I never knew. Like any student in the public school system, I was taught about atoms in chemistry class. By my twenties I fell so in love with the logic that I wanted to pursue chemistry as my life’s work. I’ve said it many times before (feel free to browse the Substack), but I completely entered adulthood with the bottom-up view of nature firmly set in my mind. (That’s one reason I love this ‘bottom-up/top-down’ distinction. It resonates.) That’s exactly what it is. If you look for it, you will see this view everywhere. Doctors treat patients as collections of biochemical molecules. Psychology is reduced to brain matter. I literally called my first two children highly complex composite systems of atoms and molecules as a new mother. I actually remember wondering why I loved them so damn much that it hurt and, yet, experiencing pain because I didn’t know what to do with that emotion or any other emotion. I remember thinking, “Emotions are not real.” Becoming Catholic was, for me, a near total rejection of everything I thought I knew. As you can see, I am still working through it.

So, I know how hard it is to reverse the order with which you view the cosmos, and I offer that personal background to emphasize why I think this work is so important. We pretty much have an entire human population that more or less thinks this way (maybe not to the extent that I did), and bottom-up thinking destroys lives, relationships, families, and societies. Thinking of the other person as a collection of particles is not conducive to healthy relationships. I don’t care how good a chemist you are, you cannot even know yourself if you think you are the atoms that make you up. Material atomism messed up a lot more than chemistry and the philosophy of nature. It derailed our search for truth.

What Next?

Leclerc gives a chronicle of how seventeenth century and later scholars addressed the contractions and puzzles of atomic materialism. I gave an overview in the previous post, but I will get into the history more via Leclerc. And I will eventually dig into Democritus and what we know of his version of atomism, which is not exactly the same as modern atomism. The goal, for me and other Thomists, is to see if we can put together—to restore—a robust philosophy of nature, and by doing so restore the dignity of natural beings. Oh yes, this all ties in beautifully to Catholic theology, but you already know that.

Until next time…

As a Catholic and as an (amateur) follower of science, I have tended to look at creation in 2 coexistent, interconnected realms: the physical universe inhabited by all matter including our bodies, governed by the physics of Newton, Einstein and the quantum physicists; and the spiritual realm, inhabited by our souls and the angels, which is outside those physical laws.

The metaphysics of Aristotle and Aquinas does not fit well, however. For example, where do forms of physical bodies reside?

I take this series to mean the view I have described above, is at best incomplete.

Your intellect may be confused, but emotions will never lie to you. Roger Ebert