Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

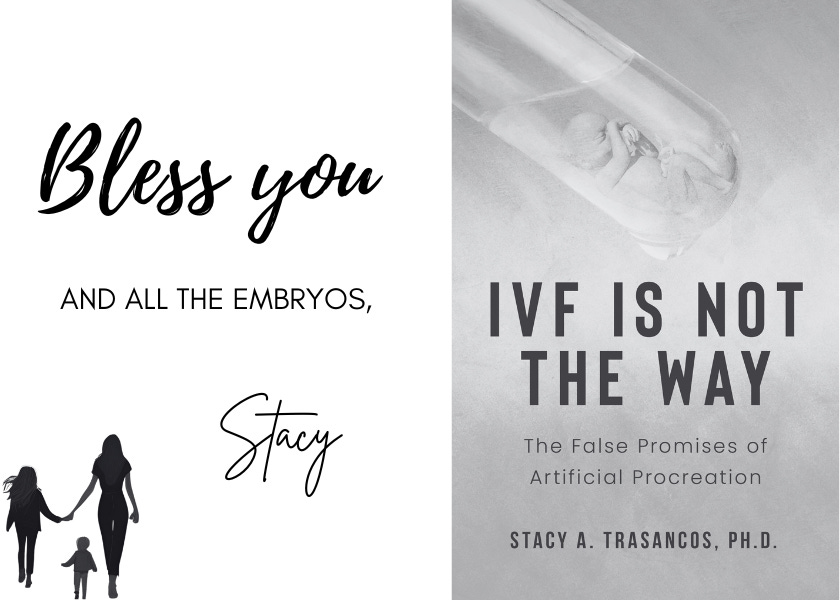

In IVF is Not the Way (Sophia Institute Press, May 2025) I finally got the chance to flesh out an idea I have had ever since I had a miscarriage—the idea of loving an embryo. This was one of the times when my faith and science clashed hard in conflict. It also was a time when philosophy helped make sense of things.

Just a “Chemical Pregnancy”

The scenario I am about to describe happens to a lot of Catholic women. If you’re not Catholic, just try to see it through our eyes. Our faith informs us univocally that children are the supreme gifts of marriage to be respected as persons:

A child is not something owed to one, but is a gift. The “supreme gift of marriage” is a human person. A child may not be considered a piece of property, an idea to which an alleged “right to a child” would lead. In this area, only the child possesses genuine rights: the right “to be the fruit of the specific act of the conjugal love of his parents,” and “the right to be respected as a person from the moment of his conception.”

(CCC 2378; Citing Donum vitae, II.8)

Donum vitae is an instruction on the respect for human life in its origin that was issued in 1987 in response to the rise of assisted reproductive technologies (ART), namely in vitro fertilization (IVF). To the question of what respect is due to the human embryo, taking into account his nature and identity, the answer is concise:

“The human being must be respected—as a person—from the very first instant of his existence.” Donum vitae, I.1

I’m a logical woman, and I remember the first miscarriage. When the home pregnancy test indicated I was pregnant, my husband and I joyfully thanked God for the gift of a new little Trasancos in the world. That’s what I said when I called him on the phone at work, too excited to wait. “Guess what? There’s a new little Trasancos!” When I went to the first OB/GYN appointment at about six weeks, everything looked good. But when I went back a few weeks later because I was bleeding, the nurse did a sonogram, and it showed a shriveled sac, no heartbeat, and an embryo that had stopped growing.

Of course, I cried. The doctor, perhaps trying to console me, said, “It was just a chemical pregnancy.” After he left, the nurse explained that chemical pregnancies are common, especially for women nearing forty, and that the embryo must have either had too many chromosomal abnormalities to grow or could not implant properly due to my hormonal imbalances. That only made me angry.

I’m a chemist. My journey to Catholicism was (and still is) a journey to reorient my atoms first, bottom-up view of nature to a top-down, essence and existence view of creation. If matter is disposed to the form, then the matter would not have been there at all unless God granted individual existence to my child along with his or her essence and, thus, form. Having chromosomal abnormalities does not change anything except that my child’s body could not grow for very long. Telling me my body failed to nurture that embryo was like a stab to my heart. What grew in me could not have been a “just a chemical pregnancy.”

Loving an Abstraction

Here’s the catch. To respect the little embryo meant I had to make myself see him or her as a person, a child conceived of our love and received in love into our family. I could not shrug off his or her death any more than I would shrug off my two-year-old child dying, God forbid. And that absolutely broke my heart. It meant I had to allow myself to love this embryo so that I could grieve this embryo.

In an abortion-mentality nation, a lot of people would not understand or would even think me insane for mourning a “clump of cells.” Honestly, it took some work. The only physiological proof I ever had of this child’s existence was a home pregnancy test and two bills from a doctor visit. I never saw the child. I never held the child unless you count holding him or her in my womb. I was in a strange situation in which I had to love someone who was very nearly an abstraction.

This personal account above is not in the book, but as it relates to the topic of IVF, I think a lot of people struggle with the same thing. How do you love an abstraction? This is where St. Thomas Aquinas helped me a great deal.

It is natural for us to love born children or to feel pain for injustices committed to born children in society because we have an emotional response to them. No one would think it is okay to suspend an unwanted toddler’s life by flash freezing him and storing him in a tank until someone was ready to raise him! This is, in part, because we have memories and sensory data of cute and cuddly toddlers. Parents can easily love their children, whether toddlers, teens, or any other stage of life (even if some days are hard). We have memories of how it felt to hold them as babies, how they sounded, how they smelled, how they looked. We have a universal idea of cute and cuddly children.

Why Bother?

In the context of IVF, however, I think it is harder for people to feel compassion for a multicellular embryo. They aren’t cute, sweet smelling, or cuddly. Emotions are good and natural aspects of our humanity, but your emotion probably does not trigger when you imagine a hundred-cell blastocyst about 0.1 millimeter in diameter, at least not as much as the idea of squeezing a fat little baby hand or breathing in the smell of baby hair. The embryonic realm is not accessible to our senses. The only one who even touches the early embryo is the mother, and she only experiences the embryo though early pregnancy symptoms. Without the brain processing sensory input and accommodating perceptions, the intellect has nothing experiential to draw upon when attempting to know and love the embryo.

In my new book, IVF is Not the Way, I contend that, for this reason, people who undergo IVF, as well as citizens in society, do not have the same emotional response to embryos as they do to born children.

As Catholics, we logically say that embryos have the same fundamental rights of any other human. Here we must appeal to critical thought, which relies on the will informed by the intellect. This appeal, in turn, pushes us to recognize the difference in our emotions and conceptions, and that exercise requires us to understand our interior and exterior senses. So, why bother with all of that?

In short, learning to love an embryo will teach you more about yourself and about what it means to love one another and pursue justice in society.

I think this case is worth making. Much of the debate about IVF focuses on the extra embryos frozen in cryogenic storage tanks, but for the same reason appeals to killing embryos in early abortions fail to convince large segments of the population, so too for IVF. The “it’s just a clump of cells” claim can seem valid, leaving people conflicted about the moral status of these embryos.

Yet, in 2024, the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that IVF embryos are children so that the parents were eligible for a “wrongful death” claim when their embryos stored in a cryogenic tank were accidentally removed from the tank, dropped, and killed. The parents were planning to dispose of them anyway in five years.

I confronted my own mental dissonance, as I said, by reading Aquinas. To conceive of an embryo and love him/her takes an intellectual exercise to go beyond what is accessible to the imagination and emotions and focus on the existence of an embryo. An embryo is anything but a non-descript clump. He or she is a proper substance, a living thing acting as one toward a natural end. He or she is human and has an irreducible, irrepeatable individuality. We, too, were once embryos. The atoms that make up our bodies may have changed over our lifetimes, but fundamentally, we are still who we were as embryos, each of us.

There is a lot (more than I expected when I started writing the book) to break down on this topic, and I hope you’ll join me as I work through it here. This information is all in the IVF is Not the Way book too, but I can elaborate on ideas more here since I am not limited to the topic of IVF.

In the end, we lost five little Trasancos’s to miscarriage. We love them all. We grieve their loss. But my husband and I also discovered more about our bond and made those embryonic children part of family’s life. The exercise helped us love each other more and to love all our children more. There are five small marble crosses on our living room mantle to commemorate our embryos’ lives. When I pray for all my children, I pray for those five too. Motherhood has taught me that every day of parenting is an exercise in letting go, whether my child dies in miscarriage, spends the night with a friend, goes off to kindergarten, leaves home as a young adult, or moves to another state. They were never mine anyway but gifts from God. My job is to give them what I can, respect them for who they are, pray for them always, and will their Good in all things.

See you next time. (Promise it will be soon.) Until then…

Stacy, our litany includes the names of the six very little ones we lost to miscarriage. The adoption of our daughter eased the pain of loss but the scars had their effect...and COVID ripped us apart.

Monica, Madeline, Emily Ann, Miriam Rosa, Oliva Marie, and James Clarence...pray for us!

Love this. Whenever a child is lost there is a missing. We don’t always know what it is and we all deal with that loss differently. As a post abortive woman (I am just recently able to say that🙏🏻) the loss was the deepest after I had healed some and could understand the existence of my child separate from my personal shame and guilt. I can imagine this is is what a woman feels after a miscarriage. It is a mourning like no other.

I have been thinking lately about all of the parents who have used IVF and the healing that will one day be needed. And what would that look like? Being forgiven and coming to terms with possibly having 10+ IVF abortions… it’s a very heavy thought. And Catholics are not immune to this lie of IVF. They are scared, desperate… they believe it will make it all better.

How well the enemy plays on our emotions and weaknesses to wound us so we give up and reject God.

So many thoughts about this….