Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

As I said in Part 2 of this short series, my new book IVF is Not the Way (Sophia Institute Press, May 2025) addresses our collective response to the millions of human embryos stored in cryogenic tanks. I argue that we must love them, in the sense of caritas and willing the Good of the other. St. Thomas Aquinas never wrote a treatise on how to love an embryo, but I apply his teaching on exterior and interior senses to the question about loving these children whom we cannot see, touch, hear, or smell. This is not a teaching on how to sense embryonic children, but rather how to push past reliance on sensation into critical thought.

This part, Part 3, covers Aquinas’s teaching on external and internal senses. We must bypass sensory data, and to do that, we must know what it is. Part 4 will wrap up this discussion about loving embryos.

Interior and Exterior Senses

In Part I, Question 78 of the Summa theologiae, Aquinas discusses “The Specific Powers of the Soul,” building on what “The Philosopher” (Aristotle) maintained in De anima (II, III). This question comes after the question about the union of the body and soul and before the question about intellectual powers, bridging these two ideas. If the body and soul are united, and the rational human soul is capable of abstract, critical thought, each affects the other. The rational soul can direct the body in certain ways. For example, we can force ourselves to remain civil even if we are ‘hangry,’ intellectually overriding bad manners if we are suffering from a missed lunch. We are also intellectually affected by our sensations; the knowledge we have of the world comes to us through our senses.

The last two articles of Question 78 address the exterior and interior senses. These surprisingly line up with what modern neuroscience has discovered about how the brain works too (see Part 2 for references to Freeman). I’ll explain. It’s kind of like a disc jockey mixing records.

The five exterior senses—sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch—are how we take in external data (perceptions) of the world into our interior senses.

The four interior senses—common sense, imagination, memory, estimation—process data from the five external senses and inform the rational human intellect.

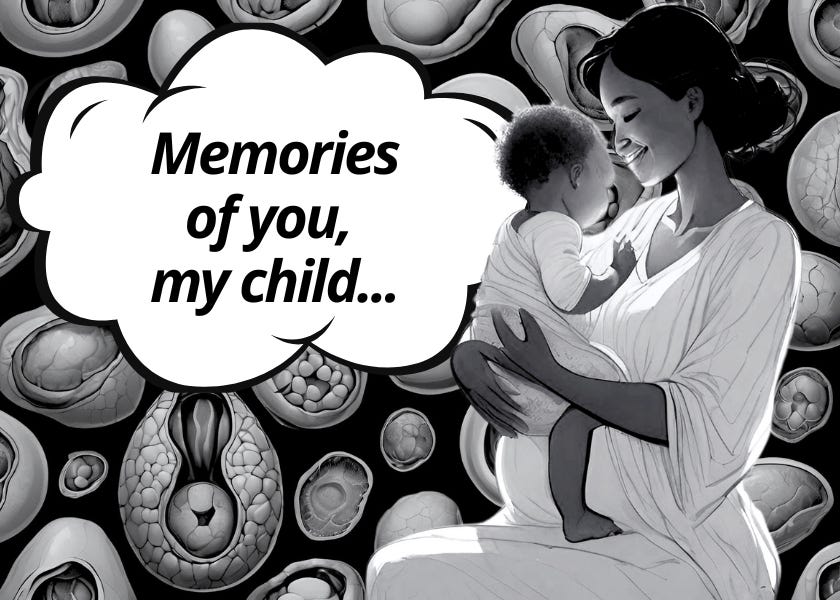

The sensory power of common sense is the ability to apprehend (lay hold of) the unity of what is being sensed by several external senses in unison. For example, when we hold a baby, we see him, touch him, hear him, and smell him all together. We don't see a baby and then, later, smell the baby, and then even later, connect the two senses. That's what “common” means here. Our brains put it all together as we take it in. Freeman describes this as individual perceptions feeding into an existing wave of cognition in the brain.

The power of imagination is the ability to retain and manipulate the forms received through the senses. The imagination is constantly at work within us, adjusting our perception of current sensory experience in the light of already received impressions, combining and recombining impressions to form images. Because the imaginative sense does not depend upon objects being actually present, the imagination can also create images that do not correspond to reality, such as fictitious stories, unicorns, or bad dreams. Ever been told you have an active imagination? Freeman explains images in the mind as derived from the existing neurological dynamic structure.

The power of memory is like imagination, but it is more specifically the ability to retain and recollect past images. Humans can do more than animals, which recall single experiences. We can reminisce about past experiences, meaning we can recall a series of situations and express them as a recollection that leads to a discovery of intentions. Using our intellect, we can reason abstractly about our past. It actually takes a lot of intellectual work and will power not to let imagination cloud the memory. That's why when people are angry and the brain is firing away, they literally need to breathe deeply to calm down so they can think rationally. Freeman does not go so far as to acknowledge an intellect that can control the imagination and memory, but Aristotle and Aquinas do.

The power of estimation (in humans also called cognition) is the ability to perceive the world around us as something to be responded to. It is awareness of our surroundings as they affect our well-being and call upon us for action. An animal knows what plants are good for food and when danger is near. We have an instinctive reaction to fire, to an angry face, or to the smell of gas. Both humans and animals have this power of interior sensation, but their way of responding is different. Animals respond by natural instinct and natural tendency. Humans do the same, but we are also different. While we certainly have instinctive reactions, we are endowed with a spiritual capacity of awareness and reaction: the intellect and will. We are thus able to form intentions with respect to both sensitive and spiritual goods, integrating both into a unified plan of action toward the good that we perceive as an end. Freeman did not go this far.

The internal senses not only build on the external senses but also on each other. What you sense commonly (putting it all together), can be later imagined. For example, you may try to still feel the whole experience with your imagination and memory of holding your baby. Imagination builds on what you already have sensed and experienced. Memory recalls past experiences. Estimation is affected by all three other interior senses and can, in turn, affect them. They all work together as “preambles” to intellect. Our external senses receive data. Our internal senses process the data as perceptions in order to form images. Our intellect then abstracts from all the particulars of these images — something animals cannot do — to ascertain what the reality is essentially, i.e., what is its “universal” or intelligible form. In turn, our intellect directs our choices. Your decision-making process is a loop in your body and rational soul.

We are rational animals, but still animals. Prior to intellectual reflection, the diverse sensory impressions that we receive chaotic all day long are processed, combined, recombined, and examined for their pertinence to our survival. We recollect what we sense, even when the thing is no longer there. You can remember how a baby smells, even years later. Dogs remember their owners. Hummingbirds return to the same feeder even after migrating hundreds of miles. Penguins recognize the unique call of their partners amid colonies of other penguins. There are abundant examples in nature of animal memory. In philosophical terms, we say that the form is retained when the material object is not there. So, the power that preserves things interiorly is different from the power that first receives exteriorly.

What does all this have to do with loving embryos?

The desire for children is part of the sensory loop that links us instinctively to the goods of nature we have experienced and for which we are made. It is something hardwired from past experiences, something God builds into us that makes us yearn to hold our own baby and that we sense instinctively as the Good. This is why loving married couples so strongly desire children.

Sensory experience keeps us tied to the external world of singular realities around us. This is realistic but also somewhat limiting.

Interior experience allows us to push past the limits of experiences. It is here that we can meet the embryo as embryo. It is an act of interiority unique to humans.

Interiority can close us in a world of our own constructing if we let imagination take over. We keep within us in potency the sensible qualities that belong to the exterior reality in actuality. In this way, the baby we hold in our arms can be ‘held’ in our hearts and minds even when he has grown into a man. This is a precious gift, but like all gifts, it carries with it the risk of possessiveness. The absence of the sensed reality—the baby that has grown up, or the baby that never was—can so fill our imaginations that we seem to own him and have a right to him.

However, human knowledge is not trapped in the cognitive rumbling around of neurological functions in the brain. Our rational, immaterial soul allows us to escape this captivity to sensory experience alone and attain, through apprehension, judgment, and reason. Then we can grasp the truth about other realities such as they are in themselves, i.e., their essential forms, their existence, and the objective relations between them.

In short, human choices are determined not by what we image or remember, but by what we know to be True and Good. Treating innocent humans in the earliest stages of development like commodities, storing them in freezers because they are not yet wanted or killing them when they no longer seem to serve a purpose, is contrary to all that is True and Good. This is not how to build a just society.

Therefore, to love an embryo, we must push past sensory memories of born infants to the truth that an embryo is too small to sense but, nevertheless, a member of the human race, one of us, deserving the respect and dignity of any other human. If we love these embryos, then we will their good.

If we do not love the embryo, and only think about what is desirable for ourselves, then we will fail to treat them with the dignity they deserve. Their dignity and rights have already been violated by the way they were produced in the laboratory. If we are going to set things right, then we must start with love and dignity.

Until next time…